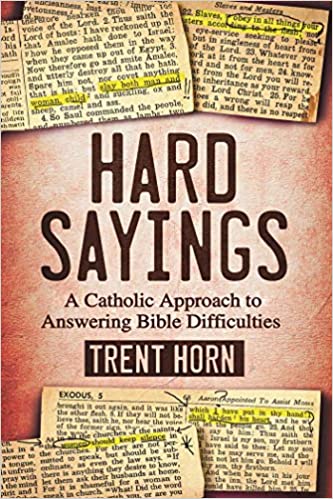

As I was first reading “Hard Sayings” by Trent Horn, I couldn’t help thinking – over and over again – where was this book during both my Protestant and atheist years, when I struggled — over and over again – with the numerous, cringeworthy accounts of blood, death, destruction, and blatant immorality featured throughout the Bible?

Better late than never, right? And that said, I am gleefully grateful that Hard Sayings is a vastly comprehensive resource on the vast array of doozy questions that Bible skeptics hurl at Christians, often framed as “Ha! Checkmate!” kinds of questions. Not to say there aren’t any other fine resources that address negative views of the Bible – other books, articles, media out there have torn apart and put back together similar answers to the questions in Hard Sayings. However, this book is probably one of the best, one-stop-shop references I have encountered in a while.

And like one of Horn’s other abundantly handy resources, Counterfeit Christs, Hard Sayings does not shy away from detailing the stinging objections that Bible skeptics raise: Horn is exceptionally good at putting himself in a skeptic’s shoes and showing crucial reasons why many skeptics are repulsed by the Bible.

One of the reasons this approach is so effective – and which applies to just about every discourse in life—is the better you know your audience, the more effectively you can shape your arguments and separate truth from bunk. Therefore, I just about always appreciate when a writer presents a clear case against an idea – as if the writer were that specific audience — and then rebuts it, rather than sweeping the criticisms under the carpet (so to speak).

Here are just some of the many claims that Hard Sayings tackles and then debunks:

“The Bible is supposedly the word of God, but the biblical God knows nothing about disease, genetics or animal classification.”

“The Bible describes fantastical, mythical beings…This shows that the Bible is just a book of myths and can’t be trusted..”

“The Bible can’t be the Word of God if it is riddled from the beginning to end with contradictions.”

“There are dozens of instances where the Gospels disagree with one another about facts related to Jesus’ birth, life, death, and Resurrection.”

“The Bible praises God for being kind and merciful, but it also depicts God as being jealous…and causing people to do evil.”

“The Bible consistently portrays women as less valuable than men, and it encourages men to mistreat women.”

Let’s take “The Bible can’t be the Word of God if it is riddled from the beginning to end with contradictions” for instance: In Chapter 9, playfully titled “1001 Bible Contradictions”, Horn emphasizes throughout this chapter – and throughout the whole book, for that matter – the can’t-be-overstated importance of reading the entire context of Scripture. It is too problematic and nonsensical to cherry pick various verses from the Bible and then exclaim, “Aha! The Bible is all about contradictions!”

Of the many examples that Horn provides, here is one to illustrate the point: Horn comments that in Dan Barker’s book, Godless (Dan Barker is a bit of celebrity in the atheist world and happens to be a former evangelical Protestant), Barker points out what appears to be a glaring discrepancy between the following passages in the New Testament:

1 Peter 2:13-14: “Be subject to the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether it be to the emperor supreme or to governors.”

Acts 5:29: “We must obey God rather men.”

As Horn explains, Peter in fact did not contradict himself – rather, Peter is instructing not to obey human institutions that oppose the Gospel. In other words, if the U.S. government decided one day to outlaw preaching the Gospel in any capacity, then we should be suspicious of the institution, that it can no longer be fully trusted. Bottom line: God first, institutions second.

Further, as Catechism 107 explains, “The inspired books teach the truth. ‘Since therefore all that the inspired authors or sacred writers affirm should be regarded as affirmed by the Holy Spirit, we must acknowledge that the books of Scripture firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided to the Sacred Scriptures.’”

That is, one of our primary goals when reading the Bible should be to connect with the overarching truth throughout all Scripture. For instance, in the above example, the overarching truth about God versus human institutions is that God is the ultimate authority over all creation, laws, institutions, and so on.

Now that we have covered just a tiny preview of the claims that Hard Sayings refutes, I suggest the following, which may sound outwardly backwards, but stick with me: Near the end of book, Horn gives a recap of several rules to keep in mind when reading the Bible. Although Horn weaves these rules throughout all 24 chapters, the summary at the end is good primer for keeping all rules in mind as you not only read the Bible, but also all chapters in Hard Sayings.

And while it may sound like I am suggesting building up biases before reading the Bible, including the Scripture examples provided in Hard Sayings, you will quickly find that the rules show how to read for overall context instead of through a narrow lens. Think about it: Don’t we read for context in other literature out there? What’s more, considering that Bible is a collection of many genres, shouldn’t it be that much more important to understand context? After all, when you understand context, you will inevitably reach the truth of the message.

Lastly, if you have read my series on “Understanding the Bible”, consider that a companion to Hard Sayings. Which means that as you develop a command of the Four Senses of Scripture, and you use solid guidelines in Hard Sayings to deal with seemingly difficult topics in the Bible, you will be that much more confident in your faith, all while discovering the amazing truths that God has revealed to us.