A couple of months ago, I exchanged emails with an atheist who, after watching my videos about my life as a former militant atheist, decided to hit me with one of the oldest challenges throughout the history of atheist thinkers / skeptics: Prove the existence of God. And to quote my challenger directly: “What is the best, single piece of **evidence** for God’s existence?”

Notice that, yes, I am emphasizing the word evidence, as that was already a bad start to the conversation. Except that I helped contribute to that bad start – and which ran through the rest of the conversation – by my keeping the word in the discussion. And though when dialoguing with atheists, I generally point out that the subject of God is philosophical – that it is NOT rooted in science – I have been guilty of incorporating the word evidence into my rebuttals, thus impeding my chances of having a more productive conversation about God’s existence.

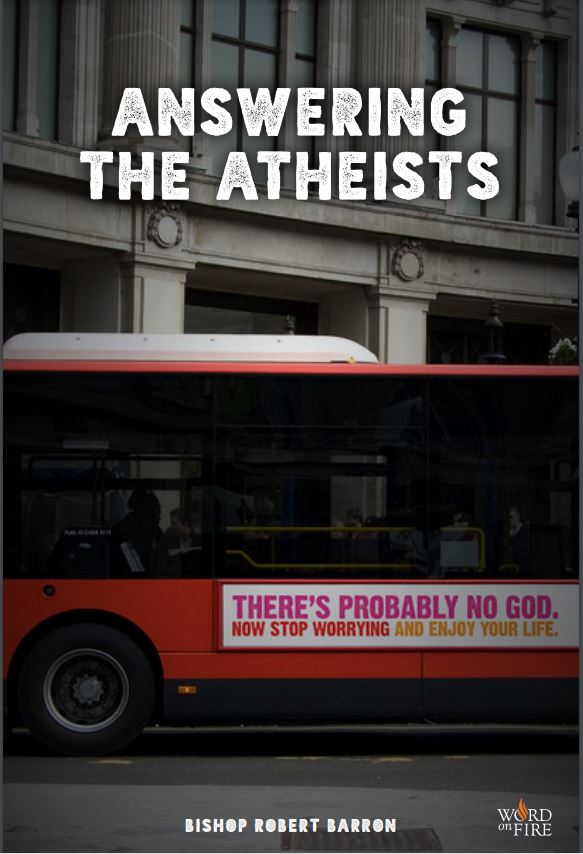

Then, just a few weeks ago, I received an email from Bishop Robert Barron’s organization, Word on Fire, about a short, downloadable booklet (PDF) called Answering the Atheists. I immediately thought, “A book by Bishop Barron, at the minimum, should help point me in a better direction when dialoguing with atheists.” I have watched many of Bishop Barron’s videos on YouTube, including videos specifically on atheism and his debates with skeptics who fall into the “new atheist” camp.

That being the case, why was I still hanging on to science related terms to discuss an idea that is outside the realm of science?

Well, the short answer is that, considering I have my own background in science, and that I spent over 10 years as a militant atheist who fell into the trap of scientism, it reminds me of the old saying, “old habits die hard”.

Yet rather than beat myself up because I have used a wrong word in a debate – I don’t claim to be a know-it-all, and I am usually willing to be corrected – I now have Answering the Atheists as another superb resource for sharing the Catholic Christian faith with skeptics and answering challenging questions. What’s more, even if an apologist already has a solid, articulate way of answering the big questions such as “What is the proof for God’s existence?”, it doesn’t hurt to have a good variety of reliable, well-researched resources to draw from whenever necessary.

Take Answering the Atheists, for instance: The booklet appears to be from a recorded interview / conversation, which was then converted into print and then polished up from there. Nevertheless, for a 22-page booklet, it packs a wallop of excellent answers to the more common questions that atheists ask: If God is the first cause, then what caused God? How can science and faith be compatible? If science has explained the reason for natural events that people used to attribute to gods (e.g., we don’t need to God to understand how the solar system works, or how the climate works, etc.), then why need a god at all? Why does God allow evil and suffering? And, of course, the overarching question I was asked in my recent dialogue: What is the evidence for God’s existence?

Let’s zoom in on that question right there: Bishop Barron points out – and this will be my go-to explanation going forward – that the word “evidence” deals mostly with science, and specifically to answer a hypothesis. As we know from the scientific method, if you want to propose an answer to a problem or question involving the natural world around us, you start by making a claim (hypothesis); you run experiments to test the claim; and if you have proven your claim correct, your conclusion fits with your original claim and is now an observable and repeatable fact.

For instance:

Hypothesis: If I throw a ball against a wall, it will bounce back in or near my direction

Experiment: I throw the ball against a wall several times, and each time it bounces back toward or near my direction.

Conclusion: A ball will in fact bounce back when thrown against a wall.

Now, that example was ultra-simplified. However, the point here is we look for evidence when testing science related claims. That works well for science – but it doesn’t work so well for philosophy. Bishop Barron explains it this way:

“Well, if that’s what you mean by evidence, I agree with them, there’s no evidence for God. Here’s the trick: God is not subject to the norms of the scientific method, because God is not a being in the world. God is rather, as Thomas (Aquinas) said, Ipsum Esse, the sheer act of “to be” itself, in and through which all things that the sciences look at come to be. The one thing you’re not going to find is God using the scientific method, because He is prior to and more ontologically basic than anything the scientists can investigate.”

Therefore, we essentially must not lean on science to have a reason-oriented discussion about God’s existence. As Bishop Barron also points out, we know many things to be true in life without needing science to prove it. And this is especially important in our current battle in Western society regarding objective truth versus subjective truth: Much of the rift among those who conflate subjective truth with objective truth involves leaning on “scientism” – and worse, it’s often bad science – to support their claims.

And while science has been a major boon to human progress and longevity, it is NOT a be all, end all guide for all of life’s burning questions. Think about it: If we can determine something to be objectively true without needing science, then, just as some atheists say they don’t need God to explain how the world works, we as believers don’t need science to explain how God works. As Bishop Barron puts it: “You can be utterly rational and not be scientific.”

Bishop Barron then suggests replacing the word evidence with the term rational warrant. That way, the conversation is then about whether we have rational reasons for believing in God. This can also help when diving into philosophy, as philosophy itself can be a bit abstract and overwhelming to digest. Moreover, it is a good baseline for dialoguing with atheists. That is, with the atheists who aren’t just playing a game of cat and mouse.

Thankfully, Answering the Atheists also addresses the other questions mentioned earlier in this post, as well as other effective ways to establish common ground first, rather than getting hyper-focused on any individual term, or having to worry about whether the atheist will try smuggling in scientism.

As with other books I have recommended, I don’t think you can go wrong with this one. It’s concise and precise in detail, and it should better prepare you for the challenging conversations with skeptics.